Published Authors and Royalties

Here is the truth no one enjoys printing in glossy brochures: royalties are not magic money. They are not applause converted into cash. They are accounting agreements dressed up as dreams, and most writers meet them the way you meet distant relatives. With hope, confusion, and a creeping sense that someone else understands the rules better than you do.

Still, royalties matter. They are the thin line between “published” as a symbolic achievement and “published” as a sustainable practice. If you plan to write more than one book in your lifetime, you need to understand how royalties work. Not in a romantic way. In a sober, slightly irritated, clear-eyed way.

This is that explanation.

What a royalty actually is

A royalty is a percentage of revenue paid to an author for each copy of their book sold. That’s it. No mystery. No applause track.

You grant a publisher the right to produce, distribute, and sell your book. In exchange, they give you a cut of the money they receive from those sales. Not the cover price. Not the number printed on the back that readers lovingly stroke in bookshops. The amount they receive after discounts, returns, and the quiet violence of distribution.

Royalties are delayed, diluted, and filtered through several layers of math. Anyone promising otherwise is lying or confused.

The myth of the cover price

New authors often assume this:

“My book costs 20 euros. My royalty is 10%. I earn 2 euros per book.”

That is rarely true.

Publishers do not calculate royalties on the retail price unless your contract explicitly says so, and many do not. Most royalties are based on net receipts, meaning the money the publisher actually gets after selling the book to retailers.

Example:

- Retail price: 20 €

- Bookstore discount: 50%

- Publisher receives: 10 €

- Author royalty: 10% of net

- Author earns: 1 € per copy

Already smaller. Now factor in returns, promotions, bulk sales, and regional pricing, and the number continues to shrink. Quietly. Politely. Legally.

Royalties are not theft. They are gravity.

Typical royalty rates

Here is the range, without comforting illusions.

Print books (traditional publishing)

- Hardcover: 8–15%

- Paperback: 6–10%

These percentages may increase after certain sales thresholds, for example, 10% for the first 5,000 copies, then 12.5%, then 15%. This looks generous on paper. It is also carefully engineered to activate only if your book performs very well.

Ebooks

- Typically, 25% of net receipts

This number looks larger, and in relative terms it is. But eBooks are priced lower, discounted more aggressively, and sometimes bundled or promoted in ways that reduce net revenue. You earn more per unit than print, but fewer units often sell at full value.

Audiobooks

- Traditionally, 10–20% of net, sometimes split further if the publisher uses an external producer

Audiobooks are booming, which does not automatically mean authors are.

Advances and why they confuse everyone

An advance is money paid to you before the book is published. It is not a bonus. It is not a gift. It is an advance against future royalties.

This means:

- You receive the advance

- Your book starts selling

- Your royalties are calculated

- You do not receive royalty payments until those royalties exceed the advance amount

If your advance is 5,000 € and your book generates 4,800 € in royalties, you will never see another euro. If it generates 6,000 €, you receive 1,000 € later, usually months later, sometimes years.

Many books never “earn out” their advance. This does not mean they failed. It means the system is structured to minimise ongoing payouts while maintaining the illusion of upfront generosity.

Advances are risk distribution tools. They protect publishers from having to pay authors indefinitely. They also lock authors into long contracts where rights may be tied up even if the book underperforms.

Payment schedules and the art of waiting

Royalties are not paid in real time. They are typically paid:

- Twice a year

- Sometimes, once a year

- Often, with a delay of 6 to 12 months after the sales period

You might sell books in January and see the money the following autumn. Or later. Or never, if the amount is below the minimum payment threshold, which some contracts include.

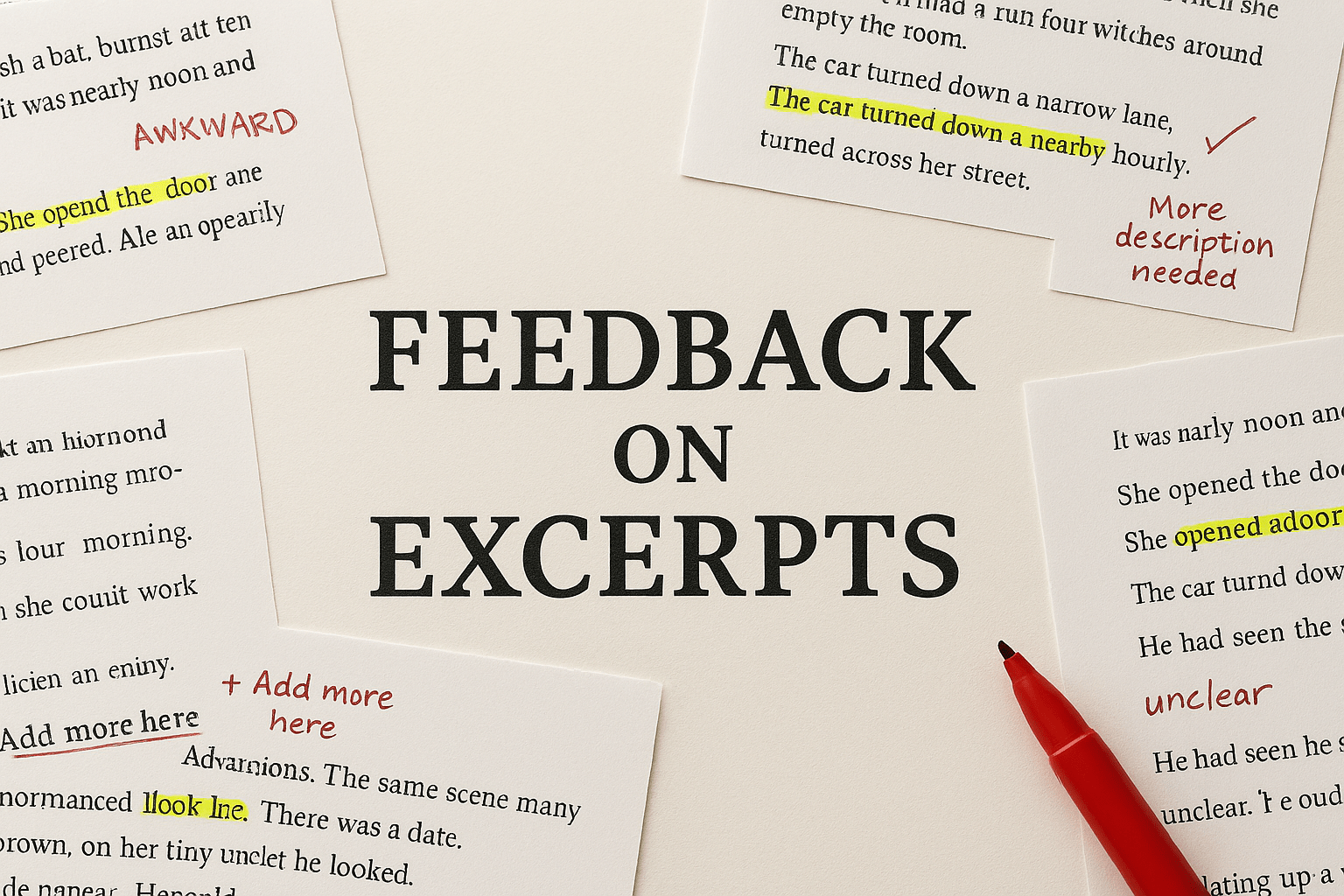

Royalty statements arrive like weather reports from a country you visited long ago. Numbers, columns, unfamiliar abbreviations. You are expected to trust them.

Most authors do. Some shouldn’t.

Returns: the invisible drain

Bookstores can return unsold copies to publishers. This is standard practice. It is also devastating.

If your book sells 1,000 copies in its first month, those numbers may later be revised downward after returns are processed. Publishers often hold back a reserve against returns, meaning they delay paying royalties just in case books come back.

You can sell well and still earn nothing. This is not a paradox. It is logistics.

Subsidiary rights and where the real money hides

The book itself is often not the most lucrative asset. The rights around it can be.

These include:

- Foreign translations

- Film and television adaptations

- Audio, large print, book club editions

- Serialisations

- Merchandising, sometimes

Contracts vary wildly on who controls these rights and how revenue is split. A common arrangement is 50/50 between author and publisher for foreign rights. Sometimes worse. Sometimes better.

Authors who do not understand rights often give them away cheaply or permanently. Authors who do understand them sometimes still give them away because leverage is a fragile thing.

Royalties are not just about percentages. They are about ownership.

Self-publishing and the illusion of freedom

Self-publishing platforms advertise royalty rates of 70% or more. This is true. Technically.

You earn a higher percentage per sale. You also:

- Pay for editing, cover design, formatting, and marketing

- Compete in an overcrowded marketplace

- Handle pricing, visibility, and promotion yourself

High royalties do not guarantee income. They guarantee responsibility.

For some authors, this is liberation. For others, exhaustion with better margins.

Why most authors don’t live on royalties alone

Even successful authors often rely on:

- Teaching

- Speaking engagements

- Workshops

- Freelance writing

- Patreon, Substack, crowdfunding

- Hybrid publishing models

- Grants, residencies, fellowships

Royalties are slow, uneven, and unpredictable. They reward longevity more than brilliance. They favour catalogues over debuts. They favour writers who keep going after the industry stops clapping.

This is not cruelty. It is economics wearing a polite face.

The emotional cost of misunderstanding royalties

Many writers internalise low royalty income as personal failure. This is unfair and inaccurate.

Royalties are shaped by:

- Distribution power

- Marketing budgets

- Retail placement

- Timing

- Genre trends

- Algorithms you will never see

You can write a remarkable book and earn very little. You can write a mediocre one and earn more. Neither outcome defines your worth or your future.

What defines your future is how clearly you understand the system you are operating in.

So how should an author think about royalties?

Not as validation. Not as punishment. Not as a salary.

Think of royalties as:

- Long-term residuals

- Delayed echoes of work already done

- One income stream among several

- A negotiation, not a reward

Write because you must. Publish because you choose to enter the market. Learn how royalties work because ignorance is expensive.

The industry runs on silence and assumptions. Writers survive by learning the language of contracts, percentages, and rights before the dream hardens into resentment.

Royalties are not romantic. But they are readable. And once you learn to read them, you stop mistaking mystery for meaning.

That alone is worth the effort.

You might want to read about:

Atmospheric & Mythic Fiction: An Essential Guide to Liminal Storytelling

Let’s Write Liminal, Dreamlike Fiction

Rethinking Authorship in the Age of Technology

Subscribe

The Inner Orbit

We value your trust!

Your address is safe in the vault.

We’ll only use it to send you letters worth opening; no spells, no spam, no secret salesmen.