or: how to stop explaining everything and let the fog do its job

Liminal fiction lives in doorways. It hovers in hallways, bus stops, half-remembered rooms. It happens when something is ending but hasn’t finished dying yet, or when something new is arriving but refuses to knock. This kind of story doesn’t sprint. It drifts. It watches. It waits until the reader forgets what they were certain of.

If you’re trying to write dreamlike fiction by “making things weird,” stop. That’s not the point. Dreams aren’t strange because they’re random. They’re strange because they feel inevitable while they’re happening, and only absurd once you wake up.

Liminal fiction works the same way.

1. Write the In-Between, Not the Event

The biggest mistake is focusing on the moment itself. The kiss. The death. The revelation. Liminal stories are allergic to climaxes. They care about the air before and the silence after.

Write the pause where someone knows something has changed but doesn’t yet have language for it. Write the hallway after the argument, not the argument. The room after the funeral, not the burial. The city at 4:12 a.m., when even time seems unsure whether it’s allowed to keep moving.

The reader should feel like they arrived too late or too early. Never right on time.

2. Blur Cause and Effect (Gently)

Dream logic isn’t chaos. It’s emotional continuity, pretending to be a plot. One image leads to another, not because it must, but because it feels correct.

Let scenes bleed into each other. Let consequences arrive before actions. Let memories interrupt the present without asking permission. Avoid signposting. If you explain why something happens, you’ve already killed the spell.

Trust the reader’s nervous system more than their rational brain. They don’t need instructions. They need atmosphere.

3. Treat Setting Like a Conscious Being

In liminal fiction, places are not backdrops. They’re participants.

Rooms remember things. Streets watch people leave. Buildings lean in when something is about to be confessed. A setting should feel slightly sentient, even if it never speaks.

Choose locations that are already transitional: hotels, lifts, waiting rooms, borders, stairwells, abandoned malls, flooded fields, archives, trains that never seem to stop long enough. These places carry emotional residue. Use it. Let the setting do half the work so you don’t have to over-write the prose like a nervous host.

4. Characters Should Feel Slightly Out of Phase

Your characters don’t need detailed backstories. They need fractures.

They should feel like they’re half a step behind their own lives, as if they’re watching themselves from a few seconds in the future. Give them obsessions instead of goals; longings instead of plans. Let them misunderstand themselves.

In dreamlike fiction, characters often don’t change. They realise. Or they fail to realise, which is sometimes worse.

Dialogue should feel almost normal, but not quite. People speak around the truth. They repeat themselves. They say the wrong thing with absolute confidence. If the conversation feels too clear, you’ve wandered back into realism by accident.

5. Use Concrete Images, Not Abstract Meaning

Never tell the reader something is eerie, melancholic, or surreal. That’s your job, not theirs.

Instead, anchor the dream in the physical. The chipped mug. The flickering light. The smell that shouldn’t be there. Specificity grounds the unreal. The more precise the image, the stranger it becomes.

Dreamlike fiction isn’t vague. It’s exact in the wrong places.

6. Let the Ending Refuse Closure

A liminal ending doesn’t resolve. It releases.

The story should stop, not finish. Leave something unanswered, but make sure it’s the right thing. The reader should feel a quiet click inside them, like a door closing somewhere far away, even if they don’t know what was behind it.

If the ending explains itself, you didn’t trust the atmosphere enough.

7. Accept That Some Readers Will Be Annoyed

Good. That means you did it right.

Liminal fiction isn’t here to be consumed politely. It’s here to linger. To follow the reader into their own quiet moments. To resurface while they’re washing dishes or staring at the ceiling at night.

If everyone understands it immediately, you wrote a mood piece, not a liminal story.

Final Thought

Writing dreamlike fiction requires restraint, which is rude in a world obsessed with clarity, answers, and tidy arcs. You have to resist the urge to explain yourself. You have to let silence speak. You have to trust that meaning doesn’t need to announce itself to exist.

Write as if the story knows more than you do.

Write as if the reader will meet it halfway.

Write the threshold. Then stop.

That’s where the good unease lives.

You might want to read more:

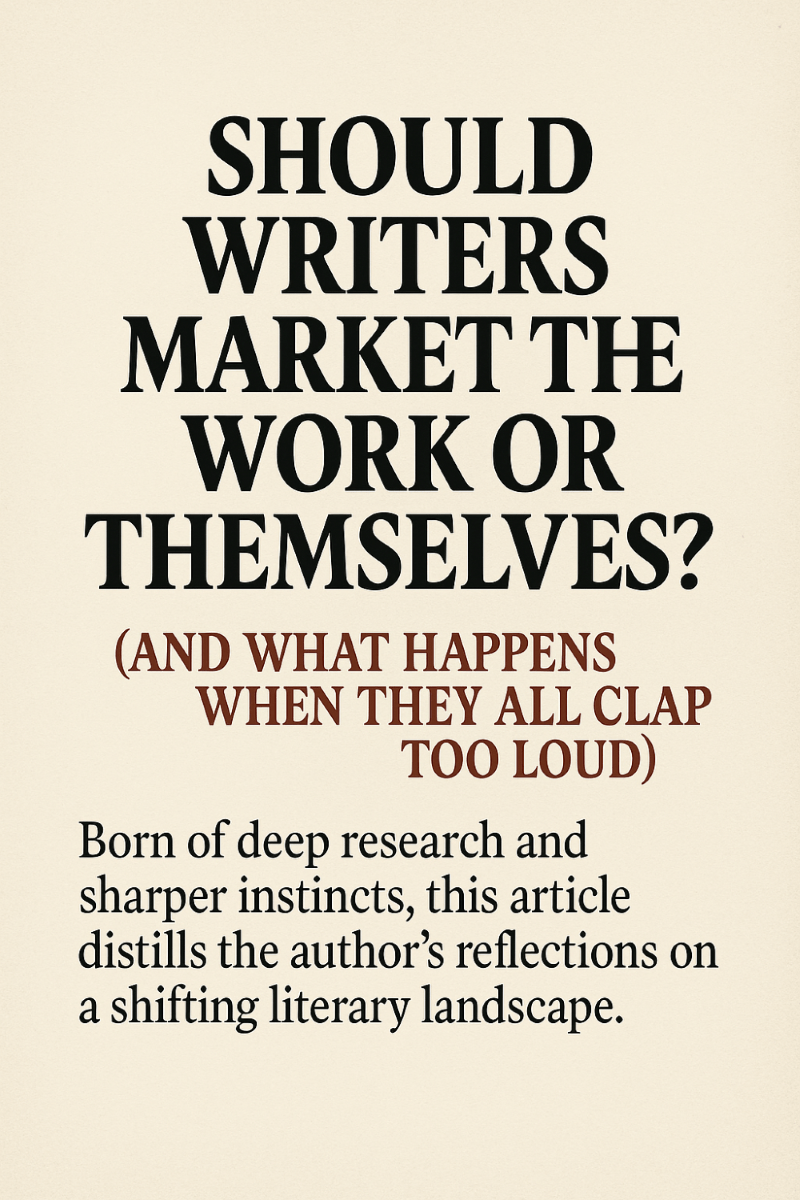

Rethinking Authorship in the Age of Technology

The Psychology of Character Desire

How to Write Emotionally Intense Fiction

The Bestseller Illusion: Why Great Writing Doesn’t Always Win

Subscribe

The Inner Orbit

We value your trust!

Your address is safe in the vault.

We’ll only use it to send you letters worth opening; no spells, no spam, no secret salesmen.