Every story pretends it’s about plot. It’s lying.

Stories are about want. Loud want. Quiet want. Embarrassing want. The kind of want a character would rather swallow glass than admit out loud. Plot is just what happens when desire bumps into reality and neither one apologises.

If you want characters that feel alive instead of laminated, you don’t start with what they do. You start with what they crave, and more importantly, why they’re not allowed to have it.

Desire Is the Engine, Not the Decoration

A character without desire is furniture. Nicely described, possibly antique, but static.

Desire creates motion. It forces choice. It makes characters lie, hesitate, betray, sacrifice, rationalise. The stronger the desire, the more interesting the moral mess that follows. This is basic psychology wearing a fake moustache called fiction.

Humans are wired to move toward pleasure and away from pain, but fiction gets interesting when those wires cross. When the thing a character wants is also the thing that might ruin them. When safety and longing point in opposite directions.

That tension is not optional. It’s the story.

Conscious Desire vs. The Real One

Most characters know what they think they want.

“I want freedom.”

“I want love.”

“I want revenge.”

“I want to be left alone.”

That’s the socially acceptable version. The résumé desire.

Underneath sits the real one. The messy, half-formed, often shame-coated need they would never put on a vision board.

Freedom might actually be control.

Love might be proof of worth.

Revenge might be relief from powerlessness.

Solitude might be protection from being seen.

Good characters pursue the wrong desire for most of the story. Great characters slowly realise it, resist that realisation, then trip over it anyway.

Psychologically, this mirrors how humans operate. We justify our actions with clean explanations while being quietly driven by older, uglier fears. Fiction that ignores this feels thin because it is thin.

Desire Is Born From Lack

No one wants things for no reason. Desire grows in the hollow left by something missing, taken, denied, or never learned.

Look backward, not forward.

What did your character not get when it mattered?

What did they learn was dangerous to want?

What did they have to become in order to survive?

That wound becomes the desire’s birthplace. Characters don’t chase goals. They chase repair.

And they almost always choose the wrong tools.

Internal Desire vs. External Goal

Here’s where many stories quietly fall apart.

The external goal is visible. Find the killer. Win the war. Escape the city. Get the job.

The internal desire is psychological. Be safe. Be valued. Be forgiven. Be real.

When these two align perfectly, the story becomes predictable. When they clash, you get friction. Friction is where readers lean in.

A character may achieve the goal and still fail the desire. Or sacrifice the goal to finally meet the desire. Either way, something meaningful breaks or heals.

That’s not theme. That’s consequence.

Desire Shapes Voice, Not Just Action

A character’s desire doesn’t just determine what they do. It infects how they think, speak, notice the world.

A desperate character sees exits.

A lonely one notices hands.

A power-hungry one measures rooms.

A grieving one catalogues absences.

This is psychology in motion. Desire is a lens. Two characters can walk through the same room and experience entirely different stories because they are wanting different things.

If all your characters sound the same, check their desires. They’re probably identical or worse, undefined.

When Desire Changes, the Story Ends

Stories don’t end when the plot resolves. They end when desire transforms.

Either the character gets what they wanted and discovers it wasn’t enough, or they stop wanting it at all. Sometimes the bravest arc is not fulfilment but release.

Psychologically, this mirrors growth. We outgrow desires or let them hollow us out. Both are endings. Only one is survivable.

Final Thought

Readers don’t fall in love with characters because they’re clever or competent. They fall in love because they recognise the wanting. The ache. The self-deception. The hope that this time, maybe, the hunger will finally quiet.

Write desire honestly. Write it embarrassingly. Write it like it knows more than the character does.

Everything else is just choreography.

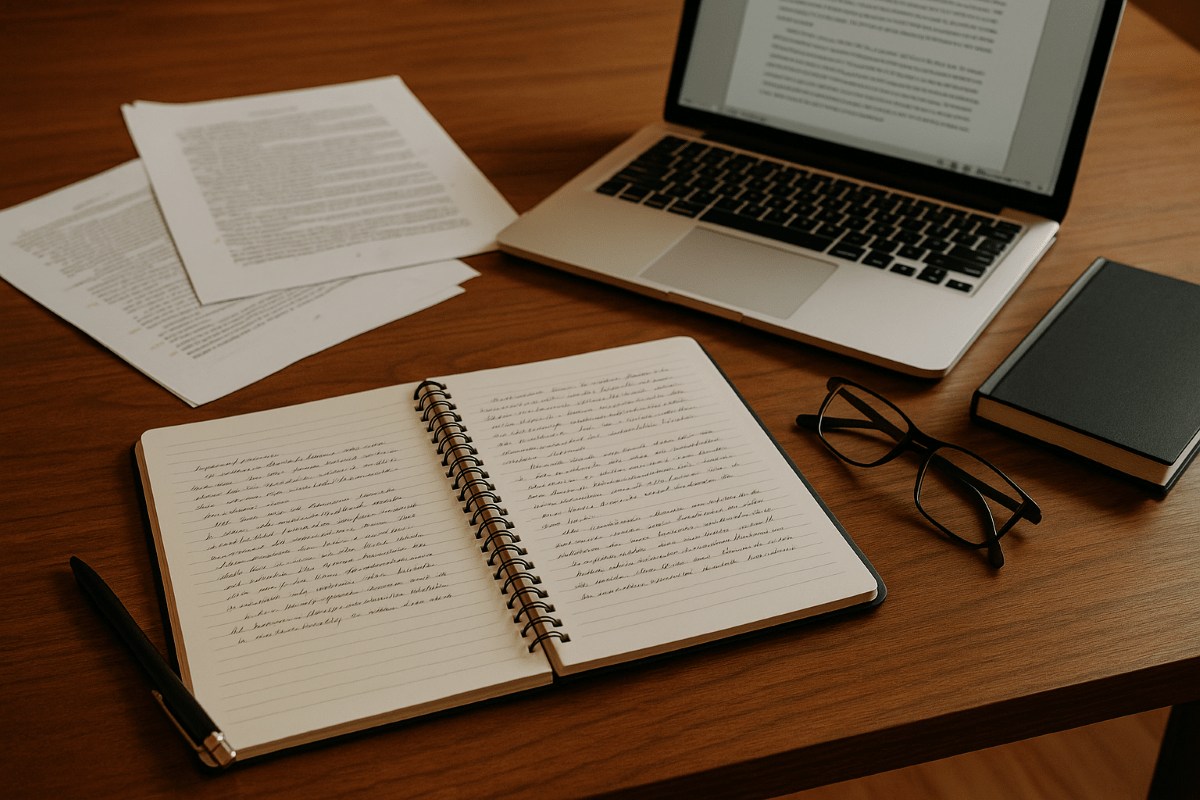

You might want to read more:

Let’s Write Liminal, Dreamlike Fiction

Rethinking Authorship in the Age of Technology

How to Write Emotionally Intense Fiction

The Bestseller Illusion: Why Great Writing Doesn’t Always Win

Subscribe

The Inner Orbit

We value your trust!

Your address is safe in the vault.

We’ll only use it to send you letters worth opening; no spells, no spam, no secret salesmen.